It has been more than a year since Asfaw last heard from his son Mesfin, who had decided to leave for South Africa. In part, Mesfin left because he was hoping to find his older brother, who had gone missing on his own migration journey years ago. He also wanted to improve his family’s living conditions. The last time his parents heard from him, he was in Malawi, when he called them to tell them he had made it that far. He never called again. Asfaw spoke gently:

“My sons were my hope. […] I am dying twice: because I lost them and because I lost hope. They used to help me till and farm the land. They were my pride. They were my hope. I am getting older and weaker.”

Many Ethiopian families have lost loved ones on migration journeys. While precise numbers do not exist, estimates from Ethiopia’s Bureau of Labour and Social Affairs suggest that nearly 6,000 Ethiopians died or went missing along the migration route towards South Africa between 2012 and 2019 alone. The International Organization for Migration (IOM)’s Missing Migrants Project has recorded the deaths of 1,073 Ethiopians on other migration routes, but the real number of deaths is likely much higher. Others may have lost touch with their families because they are held in detention, don’t have access to communication channels or for other reasons.

Last year, a research team coordinated by IOM spoke with the families of missing migrants in the neighbourhood of Kirkos, in Addis Ababa, and in Hadiya, in southern Ethiopia, to understand how the absence of their loved ones has had an impact on their lives and what obstacles they face as they search for them. Beyond this relatively small research project, there have been no other efforts to conduct research with families and communities that have lost people in the context of migration in Ethiopia.

The absence and unexplained fate of a loved one has multidimensional effects in the lives of the people they leave behind. The lack of information and certainty about the whereabouts of a missing loved one prevents families from grieving and moving on with their lives, and they have no choice but to construct their own explanations about the absence of their relative. In some areas of Ethiopia, traditional gender norms result in communities attributing the death or disappearance of a husband to the “bad luck” of the wife who stayed behind, which can have deep social implications, as Melat, the wife of a missing man, explained to our researcher:

“Truly, this is the worst moment of my life. I don’t know why God tested me. His relatives frequently blame me because they assume that my husband is dead as a result of my “bad luck”. In our community, it is very common to blame wives whenever something wrong happens to their husbands. That is heartbreaking.”

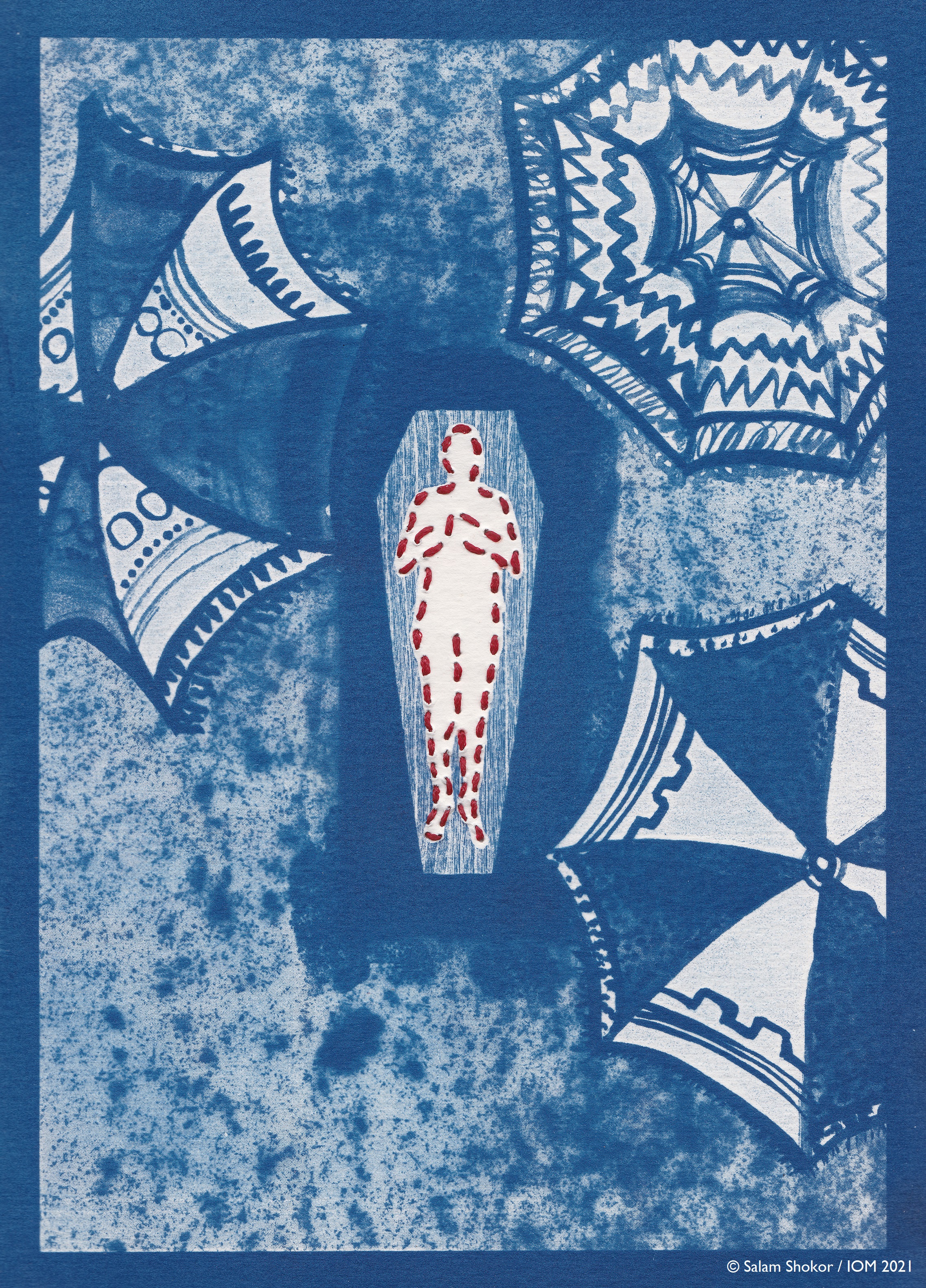

The absence of a loved one and not knowing if they will ever return leaves families experiencing an ambiguous loss that defies resolution and disrupts or freezes the process of grieving. In the absence of proof about the fate of the missing person, families cannot practice rites of bereavement, as shared by Zinash, the mother of a young man who went missing:

“I always wish I could get back his remains. […] I know death is natural, but when someone dies somewhere unknown, it is too painful. In our culture, if someone is buried without the proper cultural and religious funeral rituals, it is considered a kind of “double death”. We experienced it first when we lost him, and yet again when we were unable to perform the mourning and burial.”

In Ethiopia, tradition and religious guidelines establish that families need to bury the remains of their relatives in the graveyard of their ancestors. Families help the deceased make the transition from the living world to the world of the dead through a series of religious and cultural rites which cannot take place without the remains. Socially, it is believed that the inability to recover the remains of a missing relative means that their family is cursed. Tesema, who is searching for his missing brother, explained:

“Our grief would have not been as deep had we found our brother’s corpse and buried him in the graveyard of our grandfathers. [Worst] of all, in our community, it is believed as a huge curse for a family not to be able to get the remains of their dead family member. The whole family and their next generation will be considered cursed.”

Beyond carrying deep social meaning, absence has implications in the material conditions of families of missing migrants. Without official verification of a person’s death, relatives cannot claim inheritance or apply for state support. Women with ambiguous marital status are unable to claim ownership of the properties belonging to their missing husbands and are likely to face severe economic challenges that impact their ability to care for themselves and their children. This is reflected in the testimony of Liya, whose husband went missing on the route to South Africa:

“I can’t talk about property or inherit the land before I get proof of the death of my husband. According to the tradition, his brothers control the land. I can’t go to the courts and get into a fight with his relatives. […] I live with his relatives. I depend on them. Everything is difficult for me.”

There is an additional type of absence that is common to cases of missing migrants, and that is the absence of institutional support. The families in Ethiopia who shared their stories with IOM had not received support to search for their relatives or to deal with the impacts of the loss. If they had approached the authorities, they were dismissed or blamed for not having prevented their relatives from leaving on irregular migration journeys. Families had no choice but to push their cases forward on their own, with the support of local, community-based groups.

And yet, families and communities cannot continue to carry on these efforts on their own. State authorities bear the primary responsibility for responding to the needs of the families of missing migrants. With the support of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, IOM’s report, based on the findings of the qualitative research conducted in Ethiopia, includes policy implications and recommendations to drive action to support families of missing migrants in searching for their relatives and dealing with the impacts of their loss, including addressing the needs of families of missing migrants through a mental health and psycho-socially informed approach.

Authorities must provide families with the means to access information about their missing loved ones through an efficient, accessible, confidential and accountable process. There is urgent need for state-funded programmes to support families, which should be informed by an intersectional approach taking into account gender, age, disability, socioeconomic status, ethnicity and others. They should be developed with the participation of families themselves and/or of community-based groups representing them.

This story was written by Marta Sánchez Dionis and Kate Dearden from IOM’s Missing Migrants Project. Pseudonyms were used to protect the privacy of the families.

Find the new report “Families of missing migrants: Their search for answers, the impacts of loss and recommendations for improved support - Ethiopia” here.

"Living without them – Stories of families left behind” is a four-part podcast series produced by IOM about the research project with families of missing migrants. Listen to the first episode here.