Bangkok, 24 July 2023 – Ahmad* was living relatively well in Indonesia. Being a university graduate and fluent in English, he had a decent-paying job in information technology.

However, the prospect of a better future abroad was one he could not ignore. “Through a friend in Thailand, I received a job offer in online marketing,” Ahmad said. “The salary offer was high, so I decided to take the opportunity.”

After traveling from Indonesia to Malaysia and crossing the border to Thailand by land, Ahmed found himself in Bangkok. Not familiar with the country, he wondered in which city he would be working.

Ahmad was driven to the north of Thailand and after an hours-long road trip, he was surrounded by some armed men next to a river. He realized things were about to become bleak.

“I was so scared and confused,” he recalls. “After crossing the river, I saw another country’s flag, which was certainly not the Thai flag. I realized I had been taken to Myanmar.”

The Thailand-Myanmar border remains porous, including along the Moei River. Photo: IOM/Miko Alazas

Ahmad is one of thousands of individuals trafficked into forced labour in fraudulent schemes to deceive people online for financial gain, as part of a growing trend across South-East Asia.

While Thailand has historically been a country of destination, origin and transit for trafficking in the region, there has been an increase in the number of people being trafficked through it and into neighbouring countries, forced to work in such fraudulent operations.

Trafficking syndicates have exploited the economic impact of COVID-19 to deceive people online with lucrative job offers. In addition, the situation in Myanmar following the February 2021 military takeover has allowed syndicates to expand operations in areas with limited law enforcement presence, including along the Thailand-Myanmar border.

Like Ahmad, victims tend to be relatively educated, bilingual or multilingual, and technology-savvy.

Between 2022 and June 2023 alone, over 230 individuals representing 19 nationalities have been referred to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Thailand in relation to forced criminality, out of which 86 per cent have been identified as victims of trafficking. The actual number of victims is likely significantly higher – considering the lack of access and comprehensive information on these scam centres.

Ahmad explains how the operation worked through deceiving people on social media. Photo: IOM/Kasidit Chaikaew

Over the next half-year, Ahmad would be forced to work on fraudulent schemes aimed at scamming people through social media, posing as an attractive young woman. “My task was to collect people’s WhatsApp numbers, after which I would pass them on to another team to continue the scam.”

By all accounts, conditions in the centres are brutal.

“I would work up to 19 hours a day. We were punished if we did not reach our targets. We were electrocuted, made to stand in the heat or do push-ups or run laps,” Ahmad recounts.

Initially promised over USD 850 monthly, he only received around USD 50 per month.

Sinta*, another Indonesian, was in the same dilemma after being promised a good job opportunity by a friend. Not being able to speak English, however, made reaching her targets a herculean task.

“They kept reducing my salary when I could not reach my targets,” she says. “When I asked how I could go home, they said I had to pay back 200 million rupiah [approximately USD 13,400]. They even threatened to sell me to an organ harvesting syndicate.”

No longer able to tolerate the conditions, a group of Indonesians decided to ‘go on strike’, resulting in them being locked up in a room for two weeks.

As luck would have it, one member of the group who had secretly kept a second phone, recorded a video of their situation and published it online. The video went viral in Indonesia, gaining the attention of authorities at the highest level. With so much publicity, the traffickers deemed the group too big of a risk to keep, eventually releasing them back into Thailand.

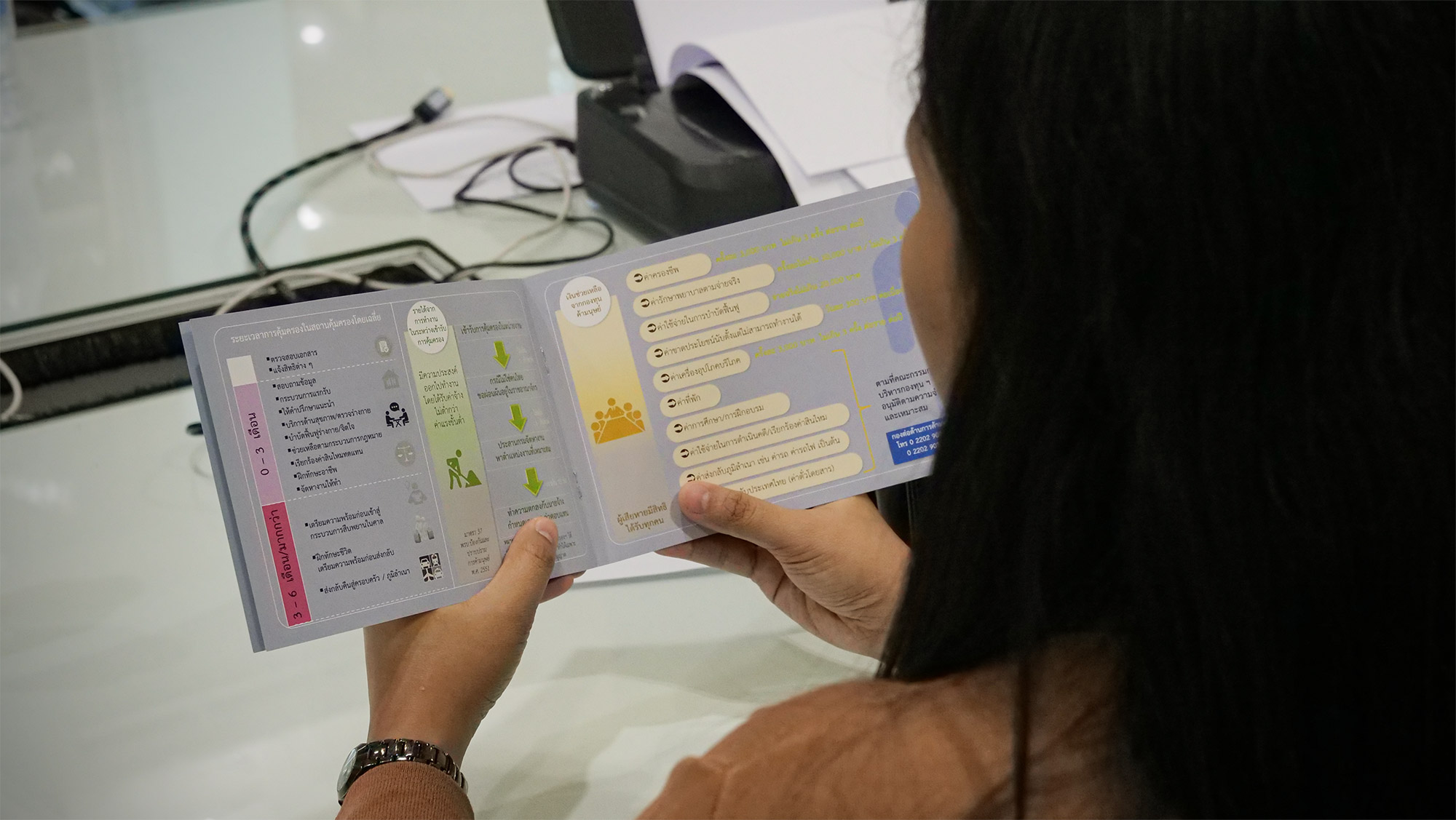

Sinta goes through a Thai Government-issued booklet, which explains the rights and support victims of trafficking are entitled to. Photo: IOM/Kasidit Chaikaew

After receiving initial support from a local organization along the border, the group was referred to the Indonesian Embassy. At the embassy’s request, IOM provided the group of 26 with food, accommodation, legal counselling and interpretation support during their weeks-long stay in Bangkok, before returning home.

“Because this emerging trafficking trend is so complex, protecting victims effectively requires strong coordination. IOM works closely with the national and provincial authorities, civil society and embassies to provide assistance when needed,” explains Géraldine Ansart, IOM Thailand’s Chief of Mission.

“Moreover, one of our priorities is to enhance capacities to accurately identify trafficking cases,” Ansart adds. “IOM supported the government last year to establish the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) on Protection and Assistance of Victims of Trafficking – a new national policy framework that stipulates roles and responsibilities in victim screening, identification, assistance and referral – and sensitized over 2,300 frontline officials on the framework.”

Without rigorous screening measures, victims can fall through the cracks, decreasing the chances of better understanding the situation and preventing others from being trafficked.

At the request of authorities or partners, IOM provides assistance to victims of trafficking – which can include food and non-food items, accommodation, medical and psychosocial support, voluntary return, and more. Photo: IOM/Kasidit Chaikaew

Now back in Indonesia, Ahmad and Sinta are taking positive stances about the future.

“My kids are aged five and two. I just want to spend time with them for now. I can leave the work to my husband,” Sinta shares with a laugh. “After all this, I have learned that I shouldn’t trust people so easily.”

“Life must go on,” Ahmad says. “I want to start a business and get my life back on track.”

Recognizing how fortunate they were to have escaped the compound, both think of those they left behind, still entrapped and unable to get out.

“For now, all I can do is share my story,” expresses Ahmad. “Through it, hopefully no one else will find themselves trapped in this nightmare, like I did.”

*Names changed to protect identities

IOM Thailand’s assistance to this group of victims of trafficking was made possible through the Government of Japan.

For requests for assistance, please contact Saskia Kok (slekok@iom.int), IOM Thailand’s Head of Protection, or thpxu@iom.int.

Story written by Miko Alazas, IOM Thailand’s Media and Communications Officer.