Hargeisa, Somaliland, 5 June 2023 – Each year, countless men, women, and children embark on treacherous journeys through the Horn of Africa, traveling along migratory routes in hopes of reaching Europe or the Middle East. These migrants traverse deserts, seas, and regions controlled by armed groups, all while risking their lives to escape violence, insecurity, or secure a livelihood for themselves and their families. However, not all of these migrants manage to leave the African continent or reach their intended destinations.

During transit, migrants are often subjected to abuse by smugglers and traffickers who keep them against their will, extort money from their loved ones, and torture them. As of the end of 2022, at least 600,000 migrants remained stranded in Libya, and an additional 43,000 were living in Yemen under extremely harsh conditions. Many of these migrants are stuck in a state of limbo, longing to return to their communities and loved ones, even if it means sacrificing their dreams of a better future. However, a lack of financial resources, information, and safe migration options often prevent them from doing so independently, leading to exploitative labour conditions and life-threatening risks.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has been working to assist Somali migrants who have become stranded in Libya since 2017. Thanks to a programme funded by the European Union, IOM has helped over 800 Somali migrants return to their communities after expressing their desire to do so. After their return, IOM provided these individuals with financial assistance, therapy, and skills training to help them rebuild their lives and address the underlying circumstances that drove them to leave in the first place.

This photo essay showcases the stories of Somali migrants who were supported by IOM to return from Libya between 2021 and 2022.

This essay is a collaboration between Claudia Rosel and Yonas Tadesse.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

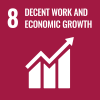

Abdijabar: Borama, Somaliland

Abdijabar left his hometown after he turned 17 years old with five friends to pursue his dream of studying engineering in Europe. After crossing through Berbera, Yemen, Sudan, and Libya, he faced torture, starvation, and the loss of two friends in Libyan detention centres.

“I was tortured. Smugglers would hit me with a metal stick and force me to eat salty food. Two of my friends died because of a lack of food,” he recalls.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

Abdijabar’s mother paid USD 12,000 to smugglers for his release, which has put a strain on their family’s finances. “My mother took a loan from a bank that she is still paying back. This situation now affects my younger brother as we can’t afford to pay for his education,” he explains.

After his return with assistance from IOM, Abdijabar received a cash grant to start anew. “Seeing my mother again and spending time together was the best part for me,” he says. “With the money I received, I purchased a tuk-tuk to help my mother repay the loan she took. However, I still haven’t managed to afford a university degree.”

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

Samater: Borama, Somaliland

Samater, 20, left his home with four friends, hoping to find a better life in France. “I was told by some friends that I would get a permanent residence and a job in France. We did not know anything, so we went to Libya to cross the sea,” he says.

“I was in detention for one year in Libya. My family had to pay USD 9,000 so I would be allowed to leave,” he says. “I survived by chance. Three of our friends died due to disease. They were 24, 22 and 20 years old.”

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

Samater tried to get on a boat to cross the Mediterranean Sea, but the authorities prevented them and others getting on board. He found out about IOM’s programme and registered to return home. “Thanks to the grant from IOM and some financial contributions from my family, I bought a small bus with my brother to start a transportation business. The business was going well, and we could make a living,” he says.

Unfortunately, a car accident destroyed their vehicle, but Samater is currently saving money by repairing other people’s cars to get his business back on track. Despite the challenges he’s faced, Samater remains hopeful for the future.

Photo: IOM/Claudia Rosel

Mohammed: Borama, Somaliland

Limited job opportunities pushed Mohammed to leave his hometown without telling his parents. “I travelled to Libya in January 2021. I wanted to go to Sweden to get a job and improve our family situation,” he says. Mohammed did not have any money to support his trip, which was not a problem initially. Smugglers know that most migrants don’t enjoy a good financial situation and usually offer them a free ride to Libya. It is once they reach Libya that problems for migrants start.

“I knew the people who brought me to Libya would ask me for money, but I still decided to go. I did not have any option at that time,” says Mohammed, who stayed in Libya for over one year, living in between different detention centres where he faced hunger, disease and torture.

Photo: IOM/Claudia Rosel

Mohammed learnt about IOM’s assisted voluntary return programme when some staff from the Organization visited the centre in which he was staying. He registered for the programme and decided to return home. With the reintegration grant that he received, he opened a grocery shop and is now self-sufficient. “I can manage my life and it helps me,” he says.

Mohammed is also studying information and communications technology (ICT) part-time at university, and the grocery shop allows him to cover the fees for his education. “I don’t plan on trying to go back to Europe. I had that experience, and I don’t want to try again,” he says.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

Kalthum: Hargeisa, Somaliland

Kalthum contacted smugglers to facilitate her trip to Italy in search of better job opportunities and to avoid early marriage. She was only 17 years old when she arrived in Libya. “I spent there three years. I faced many obstacles, like torture and lack of medical care. Life was very difficult,” she says.

To protect their daughter’s life and secure her freedom, Kalthum’s parents paid smugglers over USD 17,000. However, she got into a car accident in Tripoli upon her release, which led to her being hospitalized for almost eight months. “I was in a lot of pain, and many of my bones were broken. I also contracted tuberculosis while I was in the hospital,” she says.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

Far from her loved ones, Kalthum learned about the IOM programme that helped her return home in 2021. “I opened this small clothing shop in Hargeisa, and I hope to expand it in the future. There is a big difference between my life before and now. Most of my problems are solved,” she says.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

Abdullahu: Borama, Somaliland

“Many people died in detention, and we were helping to bury them,” recalls Abdullahu, who also attempted the Libya route to reach Europe. “They would torture you until you paid money. Then, they would call my family to tell them they were going to kill me.” His parents had no choice but to borrow USD 14,000 from relatives to secure their son’s release, a financial effort they are still suffering from. “We were given only one meal a day, usually macaroon. The smugglers would mix fuel in the meal to make us suffer.”

With the assistance of IOM, Abdullahu was able to return and start a new life. He used the grant he received to purchase a tuk-tuk, and he now makes an average of USD 10 a day, which is enough for food and fuel. “My life is better now than when I left,” he says.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

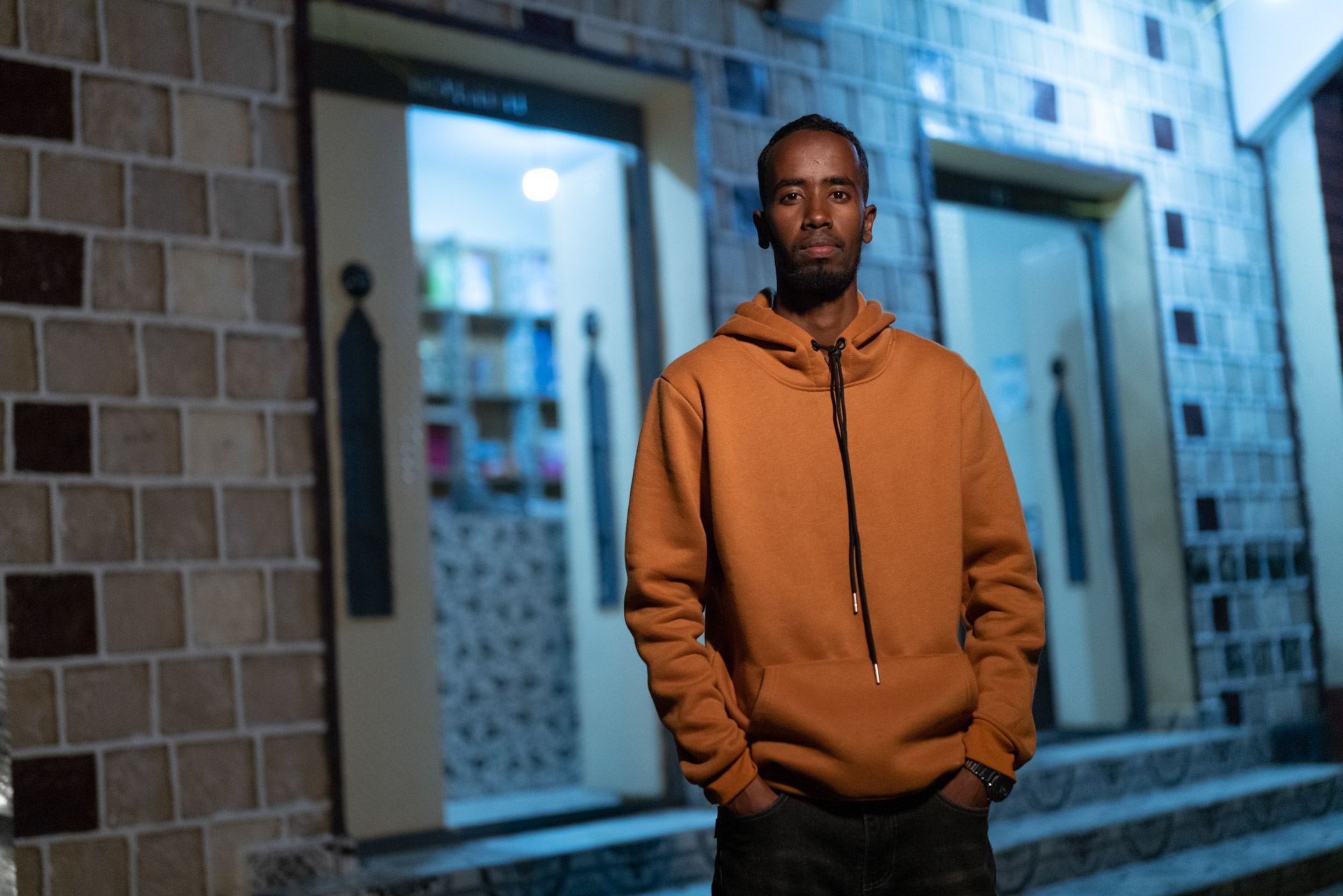

Usama: Wajale, Somaliland

“I left my hometown at the age of 18, frustrated by the lack of job opportunities for young people even with a degree,” says Usama. “But I had no idea how difficult the journey would be. People were dying in front of me, and many of my friends suffered from tuberculosis. Smugglers would even call the families of the deceased to demand money. It was as if we were treated as subhuman,” he says, reflecting on his experiences in Libya.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

Feeling homesick and longing for his family, Usama signed up for IOM’s assisted voluntary return programme. “I missed my family a lot. I learnt to appreciate my hometown, and I was very excited to see my friends, so when I was offered a chance to return home, I signed up immediately. My dad passed away shortly after I came back, and I was able to attend his burial. That was very important for me,” he says.

With his reintegration grant, Usama and a business partner opened a furniture shop. “My circumstances now are not comparable with how it was before. At least, nowadays, I have the capacity to change my life and make my own choices, thanks to this business. I hope I can expand it in the future,” he says.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

Samater: Borama, Somaliland

Samater was determined to pursue his passion for football and believed that Europe would be the best place to make it happen. At the age of 17, he left his hometown with some friends and headed for Libya.

“The smugglers would torture us with electricity or hot plastic. We had no freedom to move, and they didn’t care if you lived or died,” he says, describing the horrors he endured. Samater’s parents had no choice but to send USD 17,000 to smugglers following threats to his life.

Photo: Yonas Tadesse

With IOM’s help, he was able to return home, and he used the assistance he received to study public health. “I have already used up all the money, but now I help my parents in their grocery store or fix my neighbours’ cars to save up for my studies,” he says.