Tulcan, 30 January 2023 – Alexander Darin takes a deep breath, shoulders a backpack full of his belongings and walks across the Rumichaca International Bridge, the main border crossing between Colombia and Ecuador in the Andes Mountains.

Pushing his 3-year-old daughter Zoe’s stroller, Alexander, his wife, Francis, their 12-year-old daughter Saemi and their puppy are making the 5,000-kilometer journey from Venezuela to Chile, where he hopes to find work as a cook.

“The trip has been harsh, every day we are freezing and hungry. It is difficult to get a lift,” says Alexander, exhausted.

They left Caracas, Venezuela’s capital, a month earlier without any money for transportation. He hopes the family will succeed in their trip to Chile, which they are making “step by step”, selling sweets on the streets of the towns they pass through.

Venezuelan migrants brave dangerous migration routes in search of a better life. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortes

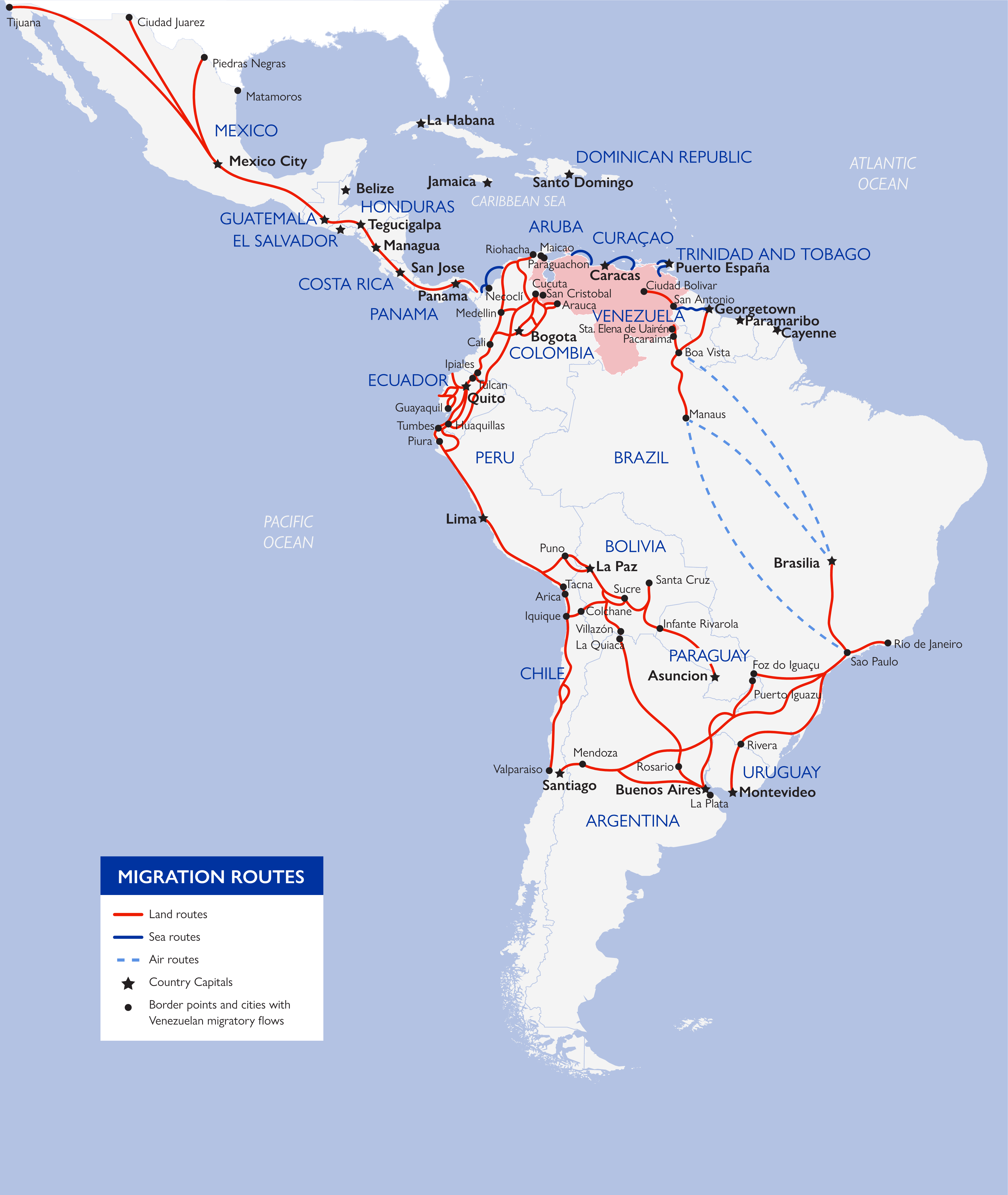

Venezuelan mixed migration flows, although not as intense as in other periods, continue into neighboring countries. More than a quarter of a million people transited through Ecuador in 2022, according to the local authorities. From there, they move throughout South America heading North bypassing formal border crossings.

The caminantes (“walkers” as they are known) travel thousands of kilometers by foot, on the side of highways, through hazardous terrain and harsh weather conditions, putting themselves at risk of all kinds of danger and threats, including criminal groups and smugglers. These risks are especially serious for young women and families carrying small children. Many travel the road in flip-flops, T-shirts, and shorts. They walk and hitchhike for months along the mountain roads that connect cities like Bogota, Quito and Lima with Santiago de Chile and Buenos Aires.

This map presents an overview of the migration routes used throughout South America and is for illustration purposes only. The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At more than 3,000 meters above sea level, the route between the Colombian border and Tulcan, in Ecuador, is covered by freezing mist and has extremely low temperatures. Fabio,* a 27-year-old Venezuelan from Valencia, tries to flag down passing lorries in hopes of getting a lift. He was promised a job in Peru and wants to send money home to the family he left behind.

“Life is unaffordable in Venezuela, there is no way you can make ends meet. I am just looking for a better future,” Fabio says after sleeping for weeks on pavement, braving night-time temperatures that can drop to 5 degrees Celsius.

Venezuelan migrants try to flag down passing lorries in the hope of getting a lift through Ecuador. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortés

IOM staff providing humanitarian assistance and information about the road ahead. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortés

Teams from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) drive a humanitarian trailer daily along the routes from Tulcan to the Colombian border, providing migrants in transit with food packages, water, hygiene kits, cold weather gear and information on the road ahead. The border is quite permeable; it is estimated that about 1,500 Venezuelans enter Ecuador monthly through irregular crossing points in search of better living conditions.

A bed for the night

At the end of a long and dangerous journey, there’s a glimpse of hope. The Hotel Quito, in the Ecuadorian border city of Tulcan, is a temporary shelter supported by IOM. As night falls, the shelter gradually fills with young couples, families with children, and lone caminantes. They receive shelter for the night, medical and psychological assistance, and three hot meals daily.

Jose, his wife, and children aged five, six and eight want to reach Perú. He is among thousands of Venezuelans who are walking towards other cities in South America. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortés

As night falls the shelter gradually fills with young couples, families with children, and lone walkers that have been traveling for days. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortés

In the shelter, a tired-looking man with his four-member family stands out among the exhausted walkers at the reception center. Jose* has a story of struggle and despair, as well as of will and determination.

He was kidnapped at the Colombian border and separated from his family for 24 hours. Now, they only dream of starting a new life in Peru. “When you hear from your kids – ‘Papa, I am hungry’ – and you have nothing to give them, it is very sad. It was also painful to leave my two older kids behind in Venezuela,” he says with a lump in his throat.

Jose’s wife, Maria,* sits with her sons among a pile of bags that hold their belongings. They have been walking for 12 hours nonstop.

“Walking is a sacrifice, but this is to help my children. If you don’t take a risk, you don’t have anything,” she says.

Migrants crossing Rumichaca International Bridge, the main gateway between Colombia and Ecuador. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortés

Maribel, 29, and her 7-year-old daughter Victoria, from Barinas, spent a year in Bogota where they survived by selling food in the streets. They now find refuge at a temporary shelter and hope to open a street food stall near the border with seed capital and business support from IOM. “I have always been a hard worker and I do not like having nothing to give to my daughter,” she says.

Maribel, 29, and her 7-year-old daughter Victoria, from Barinas, spent a year in Bogota where they survived by selling food in the streets. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortés

This pathway climbs up from Colombia to Ecuador and is used for irregular crossing (trochas) by migrants. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortés

More than 7.1 million people have left Venezuela, in one of Latin America’s largest population movements in history. Approximately, half a million Venezuelans are in Ecuador.

Source: R4V.info/December 2022

Having regained their strength after a night in the shelter, Alexander, Francis, Zoe and Saemi set off on foot, heading towards Chile, with their backpack full of dreams. Ahead, they face formidable geographic obstacles and other struggles on their way to a better life, a journey fueled by determination and courage. “We will get there with all our potential, waiting for someone to give us that helping hand to move forward,” Alexander says, waving goodbye.

Having regained their strength after a night in the shelter, Alexander, Francis, Zoe and Samei set off on foot, heading towards Chile, with a backpack full of dreams. Photo: IOM/Gema Cortés

*Some names have been changed for protection purposes.

This story was written by Gema Cortés, IOM Media and Communications Unit, Office of the Special Envoy for the Regional Response to the Venezuelan Situation.